There is so much history in China… let’s take up the challenge to cover it briefly and discover how modern China got to where it is today.

There is evidence of prehistoric man in China going back well past 50,000 years. Pottery, stonework and other signs of village life start roughly 8,000 years ago. Some of the tribes worshipped the birds and the sky as heaven. The Jade stone was highly valued and had a big impact on art, religion and culture. Metals were cast in bronze.

The most ancient stories mention a mythical “Yellow Emperor” who founded Chinese civilization about 4,700 years ago.

As described in Carter’s blog, the vast territory of China was split into many smaller kingdoms for thousands of years. It was unified by Emperor Qin about 2,000 years ago and China is named after him (in Chinese the letter Q is pronounced “ch”).

Other dynasties followed across the centuries. You might enjoy the Tang dynasty (700s) for its highly expressive pottery sculpture, or the Song dynasty (1100s) which rejected the ornate in favor of clean lines and appreciation of nature.

Geographically, China is well protected by oceans on its East and South borders, and by the Himalayas on its West. Only the North is open. This isolation is critical to understanding the country and people. China looked primarily inward, with periods of prosperous peace broken only by Mongol invasions from the North. That is why it spent so heavily on the Great Wall.

The Mongols kept invading until the Chinese finally took the initiative. They went around the Mongol front line and invaded the fertile plains of Inner Mongolia. The Mongols were forced to flee south over the Wall and into China, where the Chinese intermarried and absorbed a great number of them. The Empire had solved its greatest problem.

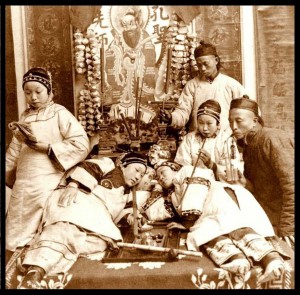

That changed in the 1750s when Britain started trade with China. The Brits wanted Chinese tea and silk, but the Chinese narrowly confined the trading. They would only accept precious metals and refused to allow the British to sell cheap manufactured goods inside China, disrupting society. But Britain was on the gold standard so they could not easily part with precious metal. So how to pay? The Chinese nobility and officials did not need slaves like America or want Western goods like India. So the British bought opium in India and used that as currency. Free samples were given to Chinese generals and government leaders.

When the Emperor finally tried to rise up against the West, he instructed his men to burn a British opium warehouse. The action reminded me strongly of the Boston Harbor tea party protest against British taxes. But the British and other occupying powers handily crushed the Emperor’s military forces during the Opium Wars. China was bullied into a series of humiliating concessions. These gave foreign visitors special privileges and set policies that allowed the West and Japan to profit at China’s expense. The Middle Kingdom had diminished to a puppet state. The foreign powers sold opium widely across China and millions of Chinese became addicts. My social studies teacher called this period “the Carving of the Ripe Melon.”

In 1850, the Taiping rebels under general Hong Xiuquan fought the corrupted Empire and managed to carve out a free state for themselves called the Heavenly Kingdom of Great Peace. They banned opium smoking, foot binding and other symbols of the Empire. They managed to hold out for fourteen years then finally the Empire crushed them. Still, “the tree had been shaken.”

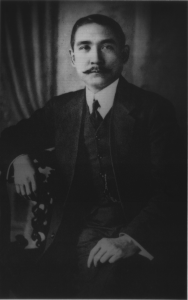

Two years later, a young Sun Yat-sen was born. Each day his elderly next-door neighbor would tell him about the exploits of the brave Hong. He began to study politics, but decided the best way he could help his country would be as doctor.

Once he began practicing medicine, Dr. Sun came face to face with the destructive effects of opium, which by this time was a pillar of the Empire’s rule. He decided to organize a rebellion. He left China for Hawaii and from there traveled abroad to build support. His three principles were nationalism, democracy and jobs for the people. In London, the Chinese convinced the British (complicit in the opium trade) to place him under house arrest, but his old British medical professor was able to get him out after a few months. In Japan, he was nearly captured but changed his name and managed to stay there for ten years. During this time he recognized that the Communists were important allies and sources of strength to overthrow the Emperor and he forged an alliance with them.

After years of sending money and organizing from abroad and mutiple failed revolts, in 1911 a simultaneous uprising across many regions succeeded in overthrowing the Empire and confining Emperor Puyi to the Forbidden City (see Katherine’s post and watch the great movie The Last Emperor). Dr. Sun Yat-sen returned to China where he was hailed as the father of the nation and elected President.

The collapse of the Empire created a power vacuum that was only weakly filled by the Nationalists. Dr. Sun struggled against various warlords, aided by his allies in the Chinese Communist Party. Years of chaos ensued.

In 1925 Dr. Sun died. His protégé and brother-in-law Chiang Kai Shek took over. Chiang did not share Dr. Sun’s allegiance to the Communists so the alliance became shaky. Still he managed to put down the warlords and to unite the country under the Kuomintang (KMT) government. (see pic of Chiang and wife)

That left only two groups standing in China – one representing capitalist democracy and wealthy families and the other Communism and the workers and peasants. Chiang decided to get rid of the Communists while he could and started rounding them up.

The Communists formed their own army, and a young man named Mao Zedong proved himself as a successful leader of a rebellion against the KMT. By the 1930s Mao was leading the Communist army but it was much smaller than Chiang’s army. The KMT chased Mao and the other Communist leaders all across China – a journey called the Long March.

During World War II, Japan invaded China. The KMT fought against Japan without much success. Chiang was hesitant to arm too many peasants and workers, recognizing them as his own future enemy once the war ended. Communists are also still bitter today that he retreated and essentially gave up three districts of China to Japan without a struggle. The Japanese committed war atrocities there. They killed three hundred thousand residents of Nanjing in just 45 days, and this is still a major source of bad blood between the two nations.

Worried about the country’s fate, or perhaps seeing that the Communists would eventually triumph, two of Chiang’s generals decided to change sides. They captured Chiang and contacted the Communists for instructions. However the Nationalists still held a much bigger army and so they kept Chiang alive. Chiang’s wife (the “3rd Soong sister”) brokered a secret meeting where she convinced everyone that killing Chiang would only perpetuate the civil war and give aid to the Japanese and foreign powers. The two sides made a pact. Under the deal Chiang was freed, one of the disloyal generals was imprisoned unharmed, one was executed, and the KMT and the Communists agreed to a mutual cease-fire that would last until the Japanese were ejected from China.

As soon as World War II was over, Mao recommenced his rebellion in full. By 1949, he had won. Chiang and the KMT fled to a small island called Taiwan.

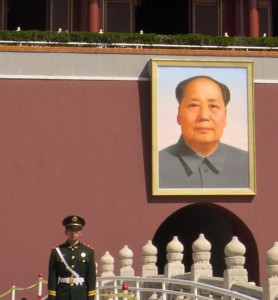

The Communist Party was now in charge of a unified China free of foreign control. Mao was most powerful and he was named the Communist Party Chairman, becoming known as Chairman Mao. The moderate Zhou Enlai was named the country’s “Premier” equivalent to our President.

The next few decades were a time of struggle around the globe between Communism and Capitalism. China was impoverished and well behind the West. Mao wanted to find a new way and from 1958-1961 he started a Great Leap Forward to harness the vast population of China for economic success. For example, he instructed people to build tiny steel mills in their back yards, trusting sheer numbers to succeed where state-owned mills had not. Land was also collectivized. During these times, Western sources report 20 to 30 million people died of starvation, one of the largest famines in human history.

After such a failure Mao started to lose influence to reformers such as the more economically open-minded Deng Xiaoping, who had also fought with Mao during the Long March and who also had a good deal of legitimacy in the Party.

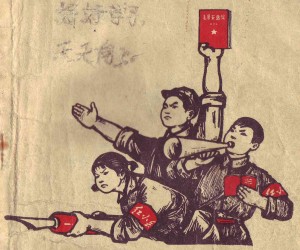

Quit? No way. Mao came back bigger and bolder than ever. He launched a nationwide program called the Cultural Revolution, making himself a political idol. Millions upon millions of students were unleashed, each carrying a little Red Book that contained Mao’s writings. They were told to travel China and destroy “everything old”. Like a hive of angry bees they went forth. The effort was driven by a Communist general named Lin Biao. Scholars were humiliated, beaten and sent to the countryside to work in the fields (an example echoed by Pol Pot). Old relics and buildings were torn down. The slate was clean, but much good was lost.

Mao used this organized mob power to purge his opposition. He twice brought down and pushed Deng out of offices. His “Red Guards” also tortured Deng’s son and left him a paraplegic.

Millions more died of starvation or hardships during these chaotic times. Meanwhile a group of senior politburo members called the Gang of Four – which included Mao’s wife – gained influence within the Party and schemed to take control after Mao’s death.

Mao officially ended the Cultural Revolution in 1969 with the country in shambles.

By 1971 there was a great deal of anger about the damage and pain from the Cultural Revolution. General Biao fled to Russia and died in a plane crash. Over the next two years the health of both Mao and the moderate Premier Zhou Enlai – still in power all the way since 1949 – was in decline.

Zhou Enlai could see the Gang of Four scheming to take control after Mao’s death. He countered this by supporting Deng Xiaoping and making him Vice Premier. Deng pushed ahead with reform, arranging Nixon’s visit to China to meet with Zhou and cracking China open once more to the West.

In January 1976, Zhou died. Deng delivered the eulogy. The Gang of Four came out in open opposition to Deng and they had an ace on the hole – the aging Chairman Mao was fully behind them.

In early 1976 there was a Tibetan revolt that was put down through force. In April 1976, tens of thousands showed up “to celebrate the memory of Zhou Enlai on tomb-sweeping day” – a holiday that honors ancestors – at Tiananmen Square. Their mass action was seen in the West as a criticism of the government and a remembrance of the moderate Zhou.

The Gang waited a few days. The Tiananmen protests dwindled to a few thousand people. Under cover of night and darkness the Gang sent in troops to beat and club the protesters until the Square was cleared. The next morning they boldly blamed the police brutality on Deng! Poor Deng was purged yet again and restricted to house arrest.

The Gang of Four’s reign was short-lived. Mao died in September. By October the rest of the Communist Party leaders had recognized the people’s anger and turned practical. Led by Mao’s old security chief, they removed the Gang of Four and sent them to trial, making them and the deceased Biao the scapegoats for everything that went wrong during the Cultural Revolution.

Deng returned and became the de facto leader of China in 1978. He was to stay in control through 1992. So Deng is the key leader who caused China to shift away from centrally planned Communism to become a global economic power today.

Just 4 foot 11 inches, Deng appeared grandfatherly. However he is described as an intense man of few words and piercing eyes who devoted himself entirely to building a better China. He ignored chit chat and spoke in a guttural Sichuan accent, sometimes bursting into anger or gesticulations. He cared little for titles. He was an “intense, crafty bridge-player” and a constant smoker. He kept a spittoon and would hack and spit freely, even in front of foreign leaders. He was an excellent debater and could reinvent himself as needed. In the early days Mao said Deng was “gentle but firm like a needle through cotton… a man with a round mind who took square actions.”

Deng could have attacked the reputation of Mao, but chose to also blame the worst parts of the Cultural Revolution on Biao and the Gang of Four. He once said Mao was 70% good, 30% bad. He preserved Mao’s historical place as a generally positive and honored figure of the Party, perhaps to show solidarity with the conservatives in the Party who would otherwise resist his reforms.

Global history was changed profoundly in 1978 during the first year of Deng’s rule. Upon taking the leadership job Deng was worried about Vietnam’s invasion of Cambodia (to oust Pol Pot, see Angkor Wat post) . He traveled outside China to Singapore, where he met Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew to discuss a coordinated Asian response. (And in fact Vietnam later withdrew from Cambodia).

While there, he was amazed that a city of overseas Chinese people had managed to become so advanced, so clean, so orderly and to provide such a good standard of living!

Lee advised him bluntly that China should stop wasting time on radical ideology and just remake itself to be more like Singapore.

Deng was hooked. He went back and created economic zones around the edges of China, essentially creating mini-Singapores in multiple locations, like lighting tinder next to logs. The center of China was rigidly controlled, while the edges were given time to adjust to the new model. A tough one-child policy was implemented, to reduce the growth of population so that economic growth could get ahead of population growth and thus improve the standard of living. By 1984 he was actively encouraging the population to change.

By the late 1980s the economic fire was lit and raging and foreign investment was pouring into China, but Deng faced two pressures. Inside the Party there was a fear that the changes were too bold and strayed too far away from the old ideology. In the streets, there was a great deal of pent up frustration coming from so much hard work, sacrifice and dissatisfaction with the government.

As the decade continued, the USSR collapsed and Russia raced ahead with a great many reforms.

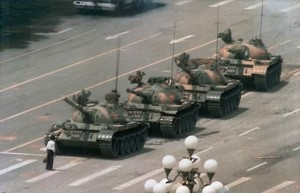

In 1989, the anger erupted in protests, centered in Tiananmen Square. One hundred thousand people showed up and stayed for weeks; a large number marched in the streets elsewhere.

Although peace was restored through the army actions, Deng lost a great deal of power inside the Communist party and China was sharply criticized by foreign powers for the use of force resulting in “hundreds” of deaths. Deng had pushed the reforms too far too fast. Conservative party leaders sent 30,000 officers through the country for the next year and a half to root out, punish and purge those with “bourgeois tendencies.” Deng resigned his official post.

But the reforms were working and growing the Chinese economy, and Deng gradually recovered his leadership behind the scenes. He played a big role in opening economic freedoms in Shanghai and this is now one of the leading cities in the world. He retained enough power to play kingmaker as others competed to run the Party, and he was able to aid those who would, could and did continue the market reforms after his death.

One source said under Deng, “GNP increased 500 percent between 1978 and 1995; per capita annual income rose from a few hundred dollars to $1,800; savings increased 14,000 percent; and export went from $10 billion a year to $153 billion.”

Since Deng the Party has been run by successive leaders who are less known in the USA. A friend suggested that this is because harmony is #1 in China, so China will always choose the calm candidate who can best keep the Party unified across divergent opinions. It sounds a lot like Japan and in fact the Party is today selecting leaders and making decisions in a more consensus oriented style rather than following a single personality.

The rest of the story centers on the economic policies of modern China. The key point is that China grew quickly by making their country highly attractive for building factories. Now they are expanding to other areas as well. But the rest of the economic story is too complicated to tell here (see Letter from China post).

Today the Paramount Leader of China is a man named Hu Jintao who made US headlines when he visited recently. The Premier is Wen Jiabao. They are mostly known for staying out of the limelight (we heard the joke “Hu’s our leader?” then “Wen’s our Premier?”). That probably means they are doing exactly what the Communist Party needs by working for cohesiveness behind the scenes.

In the future the Communist Party has said it wants to develop formal methods of selecting its leadership. I hope that will include formal checks and balances, so it can survive the emergence of future strong personalities like another Mao or for instance Putin in Russia. If that goal is ever fulfilled, it would leave China with a system in some ways similar to ours, but where the leadership is selected within the Communist Party rather than by the general populace.